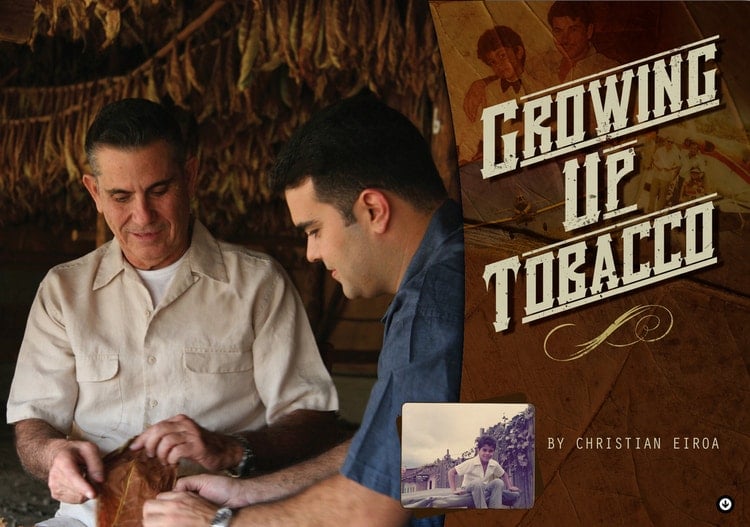

Growing Up Tobacco

My earliest childhood memory is from November 18th, 1976. It was my mother’s birthday, and I was just over four years old, living in Danlí, Honduras.

Our house was a perfect two-story shoebox, surrounded by fields and out-buildings. Inside sat my father, tying his bootlaces at the edge of his bed. He wore his blue jeans and a white V-neck T-shirt. I crawled onto his back and pressed my head between his thick, black hair and sinewy shoulders.

“Where are you going?”

“To the jungle!” he replied, standing up and setting me back down on the bed.

He tucked a .38 revolver into his back pocket and left the room for work. It was to be the only time I would clearly remember him walking: less than a year later, he survived an airplane accident that fractured his back, leaving him partially paralyzed.

I remember the day of the accident exactly as it happened; I believe it was September 20th, 1977. My sister and I had just returned from school. We received a call from our Tía Karime that he had suffered an accident and then we turned on the radio and heard the news. I was jumping up and down on the bed thinking how cool it must have been to jump out with a parachute. At just 5 years old, I did not grasp the seriousness of the matter.

At the time, my father was growing over 1,600 acres of a Connecticut seed variety named “Moonlight.” The strain was popular for green-colored Candela wrappers, and used primarily for Bering cigars, a popular brand during the 1960s and 70s. The farms were in the Jamastran and Talanga Valleys. His days were long, beginning around 4:30 AM.

After checking the pilones in the bodegas just behind our house, he’d fly to all four different farms on a daily basis.

The Jamastran, Talanga, and Tegucigalpa farms formed an equilateral triangle consisting of three 50 mile legs, as the crow flies. The dirt roads at the time were long and treacherous, plagued by mud slides and myriad other obstacles. Driving any of these legs would normally take four solid hours; the Cessna 185 Skywagon cut each leg to a mere 25 minutes.

Ater checking the pilones in the bodegas just behind our house, he’d fly to all four different farms on a daily basis.

In order to land, we’d have to call ahead by radio to make sure the workers blocked off the highway. On one particularly rainy day, we were forced to land on a soccer field. The landing was fine, but when we took off, we had to ask the players to give us a push. The propeller sprayed those poor guys with mud from head to toe. While admittedly funny from our perspective, the players thought it was hilarious, and actually lined up to give us a push the next time.

There was a whole collection of airplanes for long trips, short trips, and crop dusting. I loved walking around the hangars and sitting inside the airplanes, which included three yellow Piper Pawnee crop dusters. On several occasions I would ride just behind the pilot’s seat while he would dust. I would even go with him from one farm to another. The only permission needed was a simple call on the radio from the pilot:

“Don Julio, the kid is in the airplane again, is he allowed to go up with me?”

My father would always agree. Even after his accident, he did not want us to grow up afraid of anything.

On other days, we’d happen to catch the airplane landing. After asking the pilot to stop, we’d lay flat on the wings and hold on as tight as we could while he taxied back to the hanger.

My love of flying is tied closely to those experiences, although I must admit that I took my first lessons partly out of rebellion. Still, I came to enjoy it more that I could have expected, and immediately found a connection with my father.

Looking back on those days now, growing up tobacco was completely nuts- I mean, can you imagine a five or six year old just hopping on a plane like that?- But I loved it. My father was always fearless and aggressive. He was also tough and old fashioned: no matter what the complication or weather, he always found a way to make it home for dinner at 7:00pm and in bed by 8:00pm

My cousin Generoso “Genito” Eiroa was my idol growing up, and the inspiration for this and many other crazy stunts.

I still make it a point to buzz over the farm in Honduras just to make him upset. The last time I did it, the local battalion sent a squad over with trucks and everything trying to locate where i had dropped the drugs. My father was not happy at all about this one!

At 75, he still spends his days checking pilones and visiting the farms all day long. The roads are better now, and the farming is limited only to Jamastran. The seeds, too, have changed. Today we only grow Criollo ’98 and the Authentic Corojo Seed.

This is the example he set for me; it’s an example I draw on frequently with my own children. Today, I am the one that has carried him on my back on more than one occasion. I don’t carry a .38, but I do fly airplanes to visit a different kind of jungle. We land on runways though, not highways, and as much as I try, I cannot convince my wife to allow the boys to hop on any random crop dusting trips.