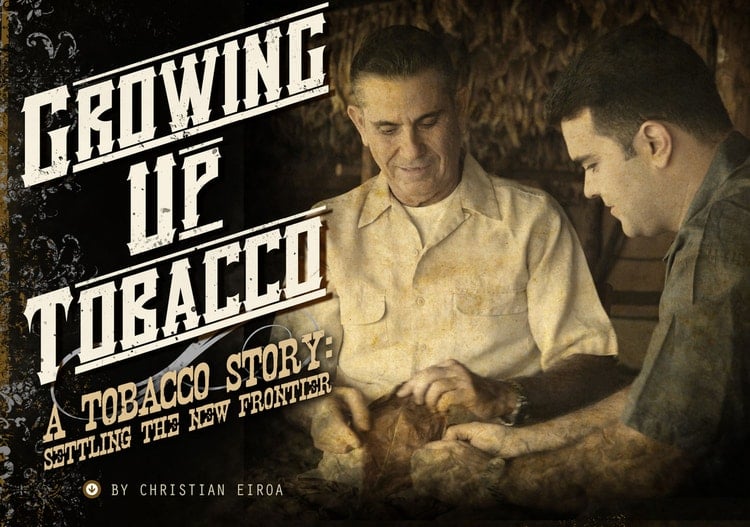

Growing Up Tobacco: A Tobacco Story – Settling The New Frontier

We have all heard stories about Castro’s rise to power and the Cuban Revolution; how his regime violently seized power and property. We’ve heard how tobacco- and cigar families fled their homeland with only a pocketful of seeds and an unbreakable will.

This is not one of those stories – well, not exactly.

This story is about two brothers whose love of family led them to Honduras’ fertile JamastranValley. It was 1960, and there was no cigar tobacco growing in Central America. But the brothers helped changed that, and in so doing, they helped pave the way for a post-Cuban cigar industry.

Their names are Generoso Jr. and Julio, and they are my uncle and my father.

Born in San Juany Martinez, Cuba in 1935 and 1938, they were close from the very beginning. But like so many brothers, their personalities were miles apart.

Generoso Jr. learned the meaning of responsibility very early. By age 14, his father’s health problems forced him to work the sorting room on his family’s 99-acre tobacco farm in the Vuelta Abajo, La Victoria del Corojo. Generoso Sr., died two years later in 1951. By 1955, 20 year-old Generoso was running the entire operation.

Despite his father’s death and the weight of his family’s business, Generoso managed to graduate from high school in 1952, and went on to complete an accounting degree from La Universidad de la Habana.

Julio, on the other hand, was a rebellious child. After being sent home from BelenJesuitHigh School in Havana, his mother opted to send him to AdmiralFarragutAcademy in St. Petersburg, Florida. Still, even at the young age of 12, my father always found time to work with his brother sorting tobacco. He looked up to his brother, especially after their father’s death, and in many ways, the farm united the brothers and their family.

My father returned from Florida in 1958 and attended La Universidad de la Habana. While studying there, he was deemed a “trouble-maker” by Batista’s government. It was a sign of the upheaval to come, and in October, 1960, the family left Cuba, hoping to return after Christmas that year. They have not been back since.

Faced with an extended stay in Florida, Julio and Generoso needed work. Fortunately, Manuel Garcia from Perfecto Garcia and Bros. in Tampa offered them jobs. Perfecto Garcia had been La Victoria’s largest leaf customer and was more than welcoming. Generoso Jr. worked in the sorting department and fixing machines, while his younger brother worked in receiving, bulk, fumigation, and blending.

Before long, my father, a true Cuban patriot, was asked to participate in the Bay of Pigs Invasion. After an unsuccessful campaign, he served out the rest of his Army days in Korea. On his return, he resumed a life in tobacco, this time with Angel Oliva, the Godfather of Dark Air Cured Tobacco.

While studying at AdmiralFarragutAcademy, my father had developed a very close relationship with the Oliva family, then a powerhouse in Cuban tobacco (and unrelated to the Nicaraguan cigar-making family). When he returned from Korea, Oliva Tobacco Company’s founder Angel Oliva invited him to go to Honduras.

Angel Oliva was the person responsible for developing the leaf trade outside of Cuba. Oliva never trusted Castro; in 1958, he saw the writing on the wall, and moved to liquidate the company’s holdings in Cuba. He sought other locations to grow the raw materials essential to his operation, beginning with farms in Florida and Connecticut. Oliva soon partnered with these farms for another operation in Honduras, where he produced wrapper tobacco.

By the time the U.S. Cuban Embargo was signed in 1960, Oliva had Central American operations in full swing. These were trying and interesting times, because Dark Air Cured Tobacco for cigars had never been grown in Central America. Neither the land nor the people were ready, and preparing each was a tremendous challenge.

Oliva sent explorers to find land suitable for tobacco cultivation. These enterprising tobacco men moved around often, planting seeds in search of the perfect location. Honduras – especially the JamastranValley – was close to Angel Oliva’s heart, because it was the only tobacco he had found to be close enough to the now unavailable Cuban leaf. My father’s job was to help process and cure the tobacco grown there by one such explorer, Tino Argudin.

After the first crop, my father decided to go on his own, and partnered with Corral Wadiska to grow tobacco for Bering Cigars. Candela was their crop of choice, specifically a Connecticut variety called Moonlight, which was dried with grills in the barns for 48 hours at 120 degrees. The end result was a bright green wrapper leaf that was most popular in the late 1960’s and all throughout the 1970’s.

If one thing is clear, it was that the Eiroa brothers share a very strong sense of family. After everything they had been through together, they would do what it took to stay together. In October, 1965, Generoso Jr. moved to Jamastran to help his younger brother, who had struck gold in the JamastranValley with powerful tobacco and most importantly, a solid customer who was also his partner.

With capital, lands, and a guaranteed customer, my father and uncle had everything they needed to become very prosperous, and set an example for dozens of tobacco growers to follow.