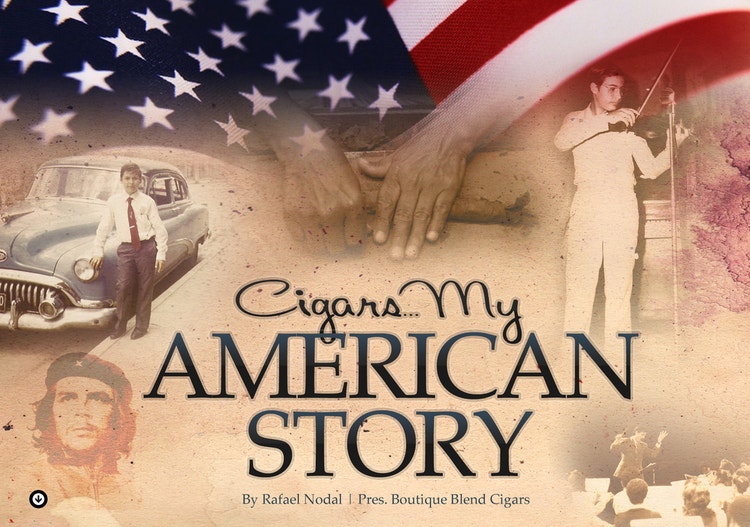

Cigars… My American Story

When we talk about premium cigars, we think of good times, good friends, good food and even good drinks, but an American story? Not really, but the history of premium cigars in America is full of stories about the American Dream. Moreover, there are very few industries that illustrate the American spirit as well as the Premium Cigar Industry.

If you smoke cigars these days, you know names like Nick Perdomo, Carlos Toraño, Ernesto Perez Carrillo, Carlos Fuente, Jose Oliva and Orlando Padrón. If you do not know my name, it will soon be familiar to you. I have something in common with all of them. We make cigars, and we are immigrants that came to this country in search of the American Dream.

My name is Rafael Nodal, and I make Oliveros, Swag and Aging Room cigars, but more than that, I am a proud American, born in Cuba.

I came to this country when I was 15 years old, looking for the same thing that all immigrants come to this country seeking: freedom and opportunity, which I call the American Dream. Not to be confused with the opportunity to have a big house, an expensive car or even a successful business. These are things that are possible only with opportunity and freedom – the freedom to work hard, the freedom to better ourselves and the opportunity to provide our children with a better future.

Some say that the dream is under attack, and I agree. However, in my American story I have faith in our country (not to be confused with the government) to make the right decisions; but that is a subject for another time.

I was born in a little town called Ciego de Avila. My childhood was as typical as the childhood of any other kid born in a Communist country. At school we had two hours a day of Communist Indoctrination, one hour before school started, and another hour before lunch; two hours a day of brain washing for every kid starting in pre-school. Two hours, if you don’t count every class that we attended, like History, Geography, Physics and Science, where we were told that capitalism was bad, the threat the United States posed for mankind, and how the virtues of Socialism, Communism and the Soviet Union were our salvation. Even math was politically fueled. How can a subject like math be mixed with politics you may ask? Leave it to the Socialists and Communists to say that 2 + 2 is 3, or 5, or 7, depending on what best serves their purpose.

In my so-called Communist “paradise” I received “free” education. Free if you don’t count that since I was 10 years old, I had to work every day for four hours and meet the daily goal of cutting the imposed amount of sugar cane, or pick the necessary amount of oranges if I wanted to see my parents every 15 days. Here in the United States, I remember when my kids were 10 years old. They were babies. Leaving them alone 30 miles from my house, working four hours a day, and being able to see them only every 15 days, could be categorized as child abuse.

On every block, there was a family whose only job was to “keep an eye” on every neighbor. These families worked under the direction of the CDR – The Committee for the Defense of the Revolution. If someone came to visit and stayed for more than a few minutes, you got a visit from the CDR. Or, if they saw that you cooked meat, knowing that the local store had been out of meat for a while, which was the norm, the CDR would call the police, because that meant you must have purchased the meat on the black market.

Every family had a little booklet that indicated what was allowed to be purchased at the store: a three-inch portion of bread per day, per family member; two pounds of rice or beans, and a pound of coffee a month for an entire family. Milk was only allowed for children under 7 years old, and soft drinks were permitted only once a year during your birthday.

The lack of food or clothes was not the worst part of living in a Communist country. It was the lack of freedom, and knowing that whatever you did to move ahead did not matter. Basically, the government wants to take away your will and your faith. There is nothing more difficult than growing up with no faith; no faith in the future, no faith in your country, no faith in God, your family, and most of all, no faith in yourself.

Then came the day when my life would change forever. It was Tuesday, April 10, 1980. I was now 15, and it was an average day. I had just finished working at the orchard and my hands were swollen from carrying the 50 pound bags of oranges for four hours. My feet were hurting from the 30 kilometer round trip each day from the school to the work yard and back. My eyes were red and I was constantly sneezing from the pesticides they used on the orange trees. Either the goal had been too high for the last two months, or I was too weak to meet it. Not doing the required amount of work meant not being allowed to go home for 52 days. So, despite my pain and hunger, I met my daily goal for the next seven days, because I wanted to see my parents that coming weekend. But I didn’t have to wait until the weekend. On that fortuitous April day, my father came to my school to pick me up with the excuse that my mother was very sick. As I would soon find out, I was actually one of the luckiest 15-year-olds in the world.

If you have seen Al Pacino in Scarface, then you know about the Mariel Boat Lifts. In a matter of three months 125,000 people came in boats from Cuba to the United States entering mostly through Key West. It all started when Fidel Castro became angered at five people who had broken into the Peruvian Embassy in Havana, following which, the government of Peru granted them political asylum. On live TV Castro announced that he was removing the government guards from the Peruvian Embassy, since the guards were there to protect the embassy, not to prevent people from asking for political asylum. In less than a few minutes, while Castro was still talking on TV, more than 10,000 people rushed into the Peruvian embassy compound.

This infuriated Castro even more. A few days later, again on live television, Castro said the people who had rushed to the Embassy were obviously criminals, mental health patients, antisocial-types, and homosexuals, because no person in his right state of mind would want to leave the Communist island paradise. He added that if any person living in the U.S. wanted to come and pick up their antisocial family members, he would allow them to leave the country. The only other way out was if you had papers signed by the CDR certifying that you were antisocial, homosexual, a criminal, or had a mental health disorder. The regime also used the opportunity to empty the prisons; this would show the world that only criminals would reject such a utopian paradise.

A friend of the family who had left Cuba for the U.S. in 1972 promised my father that, given the opportunity, he would return and pick us up. But before we left Cuba, we were under house arrest for 30 days, twenty of which were spent in an old baseball stadium that had been converted to a prison, where we had to sleep on the grass, and relieve ourselves on the floor.

Fortunately, our friend kept his word and came for us in a rented shrimp boat. I’ll never forget the name of that rusty old bucket either; it was “The Lady Lynn.” After four days at sea, during which time we saw hundreds of bodies floating in the Florida straights, I arrived in Key West on May 31, 1980 with my father, my mother, my little sister, ten friends, and 280 criminals that had been taken directly from prison to the boat.

A week later, we were given airline tickets from a religious charitable organization so we could relocate to New York City, where my father had another friend. This was not unusual, since there was a big effort to have some of the 125,000 Cubans relocated to other parts of the country in order to minimize the impact of so many new people in the metropolitan Miami area.

For three years I lived in the crime-ridden Washington Heights area of Manhattan, where I attended both High School and Music School. (I had studied violin since I was six years old.) The adaptation to my new environment was hard, to say the least. Learning English and getting used to such a big city after spending my life in a little town was not easy. But what came very easily to me was being able to move about town freely. To be able to discuss my political and religious views openly and not have to worry about going to prison. The first time we had visitors in our apartment and no one from the CDR showed up to check on us, that was the day I knew I was free.

In high school I organized musical events, and in music school I continued studying violin while taking piano classes. I was selected to be part of the Five Borough Orchestra, and played recitals at Carnegie Hall. Eventually, I was accepted into the Manhattan School of Music, where I studied with some of the most incredibly talented students and teachers I have ever known-all dreams I could never have realized in Cuba.

Then I began practicing for a conductor audition at the Juilliard School of Music. Unfortunately, it never happened. The cold city winters had become intolerable for my mother, who was recuperating from an accident some years earlier. In June of 1983, 35 days before the audition, my family’s American story took a turn – and we moved to Miami.

I like to think that I would have passed with no problem and received a scholarship. After all, I had spent a year studying Brahms’ Symphony No. 3 in F Major for my audition. Because my bedroom had no heater, I practiced in the bathroom every night for hours with an old record player I had dug out of the garbage. But, knowing all the sacrifices my parents made to get to this country, I did not want to be away from them.

In 1983, Miami was a small immigrant city, not the trendy international city that it is today. South Beach was a retirement community infested with drugs and crime, products of the criminals sent by Castro. There was no symphony orchestra either; so far, my classical music career did not look good.

I decided to enroll in Miami Dade Community College as a Music Education major, and found my first real job cleaning floors in a South Beach hospital. Between school, a full time job, an amateur opera group that I directed, and a few violin students, I had almost no time for anything else.

Cleaning floors was quite an education. Little by little I learned about other hospital departments, and worked my way into management. It still amazes me: only in America can someone go from being a janitor to the Executive Director of a national healthcare company.

During my tenure as Executive Director, I met two people who would be instrumental to my involvement in the cigar business: Hank Bischoff, and my wife, Dr. Alina Nodal Cordoves. Hank had a real love for everything Latin, especially cigars, and Alina was descended from three generations of tobacco growers in Cuba.

Together Alina, Hank and I started an online retail cigar site in 1997. Then, in 2002 we formed a company in Miami Lakes to distribute Oliveros Cigars.

Oliveros Cigars had been in the market for many years, but was known during the cigar boom as a flavored cigar line. We expanded the line immediately with several releases of premium cigars, like Oliveros Classics, Gran Reserva and Oliveros XL for Men.

Sales increased annually, but not to the extent we wanted or needed. . Many of my friends and family members insisted that we go back to the more profitable business of health care. But I was determined to make Oliveros a success. We kept trying harder and worked longer hours. We visited more stores and participated in more cigar events. Failure was not an option. As a result, I missed most of the birthday parties and school events for my three children; these are moments that you can never get back.

In 2009 it became even more difficult to survive, especially after the administration at that time increased the cigar excise tax for a government-funded health insurance program for children known as S-CHIP. During this period, I could barely sleep. It did not matter how hard we worked, things were not getting any better. That’s when I realized the truth in the saying, “It gets worse before it gets better.”

One Friday night I found myself having a cigar in Miami Beach with Hank. We were celebrating being able to make the week’s payroll and discussing the future. After sitting quietly for what seemed like a few hours (in reality it was only 20 or 30 minutes), it came to us. It was as if both of us had the exact same thought simultaneously. We were competing with the big mass market cigar producers by trying to make cigars for everyone, from the novice to the avid aficionado.

I still remember the precise moment when we both said the same words at the same time, “We were wrong.” Maybe the aroma of a nearby Cuban restaurant was driving us crazy or maybe the continued sounds of the waves was hypnotizing us, but we kept repeating “We were wrong, we were wrong.”

So it was decided. We were no longer going to make cigars for “everyone.” Instead, we would introduce some of the small batch blends that we had been working on for years, but had not introduced into the market; the reason being, there was just not enough tobacco to support a large production. We were going to produce new blends for educated consumers looking for cigars with complexity and character. And that’s how “Boutique Blends Cigars” was born.

Things are going extremely well for us today. Our new focus on small boutique blends is paying off. I am extremely grateful to all the retailers that contact us to let us know how well the cigars are doing in their stores, and the consumers that call or visit us at the cigar events to let us know how much they enjoy our cigars.

More than anything, I am grateful to this nation for giving me and my family the opportunity to earn “The American Dream.” I have learned to not give up, to work hard, and when failure is not an option, it can only lead to success.

The next time you light-up to enjoy one of your favorite premium cigars, it may remind you of good times with good friends, or fine food and drinks. Hopefully, it will also remind you of The American Dream.