Tobacco Farming: Planning & The Right People Pay Off

Tobacco Farming: Welcome to the world of Perdomo Cigars

Estelí, Nicaragua: 4:45 AM. The air is crisp, the sky clear, and the sun has just begun to reveal itself. Nick Perdomo Jr. takes in the breathtaking view of the horizon as he walks through one of his tobacco fields. In the distance, a cottony blanket if low clouds hangs listlessly between the base of the mountains and the valley below. It’s the middle of the tobacco growing season, and Nick is paying his daily visit to check on the tobacco plants. The fertile black soil on which he stands is a bold contrast to the vibrant green of the tobacco leaves that surround him. Nick lights a cigar and smiles as he watches the leaves rise up to greet the warm Nicaraguan sun.

In the beginning…

It all started in February of 1998. The day was typically hot and sunny in Estelí. I was sitting in my office with my late dad, Nick Sr., at an old wooden table sampling cigars, and they wouldn’t burn. One after the other, these things were like fire suits. Frustrated, I looked at my Dad and said, “That’s it. I’m tired of it. We’re going to do this ourselves.” He looked back at me with his big brown eyes and agreed that it was a great idea.

We were buying most of our tobacco from brokers at that time, and this one particular broker did me wrong; about $300,000 wrong. It was his tobacco that we used to make the fire-proof cigars. After some investigation we found out that they used pure nitrogen in the ground to accelerate the growth of the leaf. Believe me, things like this are not unusual in this business. There are some really great brokers out there, but then there are a few that aren’t really great either.

Take fermentation for example. You can ferment the leaf as much as you want, but once the tobacco stops heating up, the cellular structure is completely fermented. At that point, you hit the wall. Tobacco must be properly cured, aged, and fermented, and in the end should blend perfectly. With all that nitrogen they used in that brokered tobacco, there was no way those cigars would ever smoke right. And that’s when I said, “Enough, we can’t continue doing this.” It was time for our company to control its own destiny. Looking back on it now, I feel like I should thank this guy. It was a hard lesson, but it’s what would fundamentally change Perdomo Cigars for the better in the late 1990’s.

The advantages of having three fertile valleys…

Before I get into how we developed our farm in Estelí, I want to tell you about the geography of Nicaragua, and why it’s so ideal for tobacco farming.

The valleys in Nicaragua are all fertile, and each serves a different purpose. What’s sets Nicaragua apart from any other country (outside of Cuba before 1959), is that the regions are so far apart, they produce different types of tobacco with their own distinctive flavors.

Estelí is known for its great “strength” tobacco. It’s high in the valley, about 2800 ft., so you have tons of sun exposure and very thick, coarse grounds that are pitch black with soil that’s dense and cakey. It’s ideal for Ligero, Viso, heavy binders and heavy sun grown wrappers. Estelí can only produce a limited amount of wrapper though, because the region has a tendency for high velocity winds, especially in January and February, which is the middle of the growing season. All that aside, the final product consists of the most tasty, powerful fillers; there lies the secret behind great Nicaraguan tobacco, and why it distinguishes itself way ahead of Honduran, Dominican, and even Cuban tobacco, for that matter.

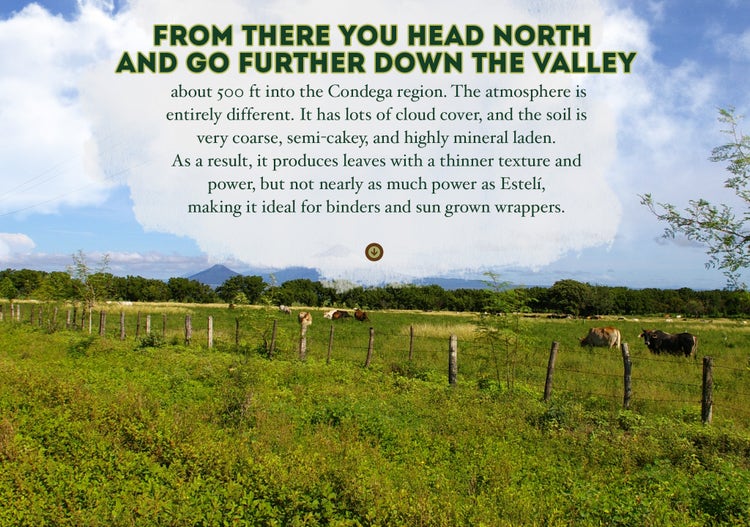

From there you head north and go further down the valley about 500 ft into the Condega region. The atmosphere is entirely different. It has lots of cloud cover, and the soil is very coarse, semi-cakey, and highly mineral laden. As a result, it produces leaves with a thinner texture and power, but not nearly as much power as Estelí, making it ideal for binders and sun grown wrappers.

Continuing north for about an-hour-and-a-half, you enter the Jalapa valley. By now you’ve dropped down to about 2000 ft. The soil there is a very thin, sandy loam, much like you would find in Cuba. The tobacco leaves are reddish and produce more of an aromatic, sweet tobacco. If I gave you a hand of tobacco grown in Jalapa and told you to smell it, you’d notice that it smells like fresh honey-wheat bread. A hand from Estelí would smell very strong, while a hand from Condega would have a little of both, strength and sweetness. That’s the beauty of Nicaraguan tobacco. All I can add to that is, when God said, “I’m going to produce cigar tobacco,” it wasn’t Cuba, it was Nicaragua.

The old man and the seed…

Now that the pieces were beginning to fall into place, I needed to learn about growing tobacco. I knew the art and culture of it; after all, I grew up in it…

I remember walking with my father through the dusky curing barns, the rich, powerful aromas of the pilones, the honey-like aroma of tobacco aging in old oak casks. Sometimes my father would grab a hand of fermented tobacco, spread it apart and have me stick my face in it. All of those earthy, robust and sweet aromas hitting you at once. It’s exhilarating. I can still hear the clattering of the rollers in the factory, heads tilted downward as their chavetas cut perfect arcs across each delicate wrapper leaf.

In my opinion, Aristides is the best man in the world growing tobacco; not only from a seed standpoint, but from an agronomy standpoint. Whether it’s curing, sorting, selection, fermentation, whatever, this guy is amazing. He even looks like an old tobacco man with his straw hat, creased, sun-tanned face, and a cigar perpetually in his mouth. At 83 years-old, he smokes 20 cigars a day, he can raise a 100 pound bale of tobacco over his head, and between all of his duties, he probably walks about 10 miles a day. One of the more entertaining things about Aristides is he says “ALABAO” a lot. That’s his word, “ALABAO Chico!” He says it almost every other word. It’s a well-known Cuban expression for “WOW!” If you ask him something like, “Aristides, how’s the tobacco today,” or “How’s everything going?” he’ll say “ALABAO!” That’s actually how we came up with the name for our Perdomo Alabao cigars.

What I love about Aristides is, he’s an open book. Next to my Dad, I’ve probably learned more about tobacco from him than anyone. If I were to bring someone down and tell him, “This is my friend ‘so-and-so.’ He’s going to be staying here for two months,” Aristides would teach you everything he knew from when he was a kid all the way on. Most older tobacco farming people have a lot of knowledge, but they tend to be closed-minded; they don’t want to teach people, and he has. But I’m not fooling myself. After all, he’s 83 years old and in great shape, but he’s not going to be around forever. So, what we’ve done is build a team of knowledgeable people who are learning from him every day. As great as Aristides is, we have a lot of outstanding people behind him; so when he finally decides to retire, we’ll be in good shape with the people he’s mentored, and the company can continue to move forward.

If you build it, the tobacco will cure…

Eventually, I decided to build my first curing barns, but I wanted to do something entirely different. I was going to build them on my own property. People thought I was out of my mind, but the logic was, we could load the tobacco on a truck and bring it into the barn where we could monitor it 24 hours a day. We built three barns, each capable of storing a very large amount of crop. The barns are 85ft wide by 130ft long covering over three acres of land. I think they may be the biggest curing barns in Central America.

After our first season we grew a fantastic crop of tobacco. Not only was it a fantastic first crop, it burned fantastic, it tasted good, it was consistent, and I said, “This is awesome, this is what we have to keep doing.”